When ChatGPT launched in November 2022, it marked a clear inflection point in technology. Many people remember exactly where they were when they first tried it. I was on vacation in Jaipur in early December, asking ChatGPT about local handlooms and helping my wife evaluate carpets within hours of signing up.

What stood out even then was not just the quality of answers, but the speed at which a general-purpose model could be useful in everyday decision-making. Fast forward to today, and large language models no longer just answer questions. They plan, reason, and increasingly take action.

In November 2024, Anthropic released the first Model Context Protocol specification, alongside Claude as one of the earliest MCP-capable hosts. Since then, we have seen a rapid acceleration toward agentic systems across nearly every enterprise function. Capabilities that once felt implausible are now routinely demonstrated. Agents draft code, analyze legal documents, triage customer issues, and orchestrate workflows across tools.

As with every major technology shift, progress has been accompanied by concern. AI may be the largest megatrend enterprises have faced, and uncertainty around its risks is natural. Cybersecurity companies, including WideField, have a responsibility to surface real issues. At the same time, those risks need to be clearly scoped and grounded in reality.

This blog is a pragmatic attempt to frame where enterprises actually are in their AI journey, how the security surface expands as adoption deepens, and which controls matter at each stage. It is not intended to be alarmist. Instead, it aims to provide a structured way to think about agentic AI risk.

AI Adoption Is No Longer Early

AI adoption in the enterprise is already widespread. Microsoft has shared that roughly ninety percent of Fortune 500 companies have deployed or are actively deploying Copilot. Google reports hundreds of millions of Gemini users across SMBs and enterprises. ChatGPT Enterprise and Claude have also made meaningful inroads with knowledge workers.

In practice, most enterprise employees today have access to at least one AI assistant. Often, they have access to more than one. Whether that tool is their preferred option is a separate question, and one that becomes relevant when we talk about shadow usage.

More important than adoption numbers is the pattern behind them. Enterprises tend to follow a fairly consistent path in how they deploy AI, building on foundational identity security principles that have become increasingly difficult to ignore as environments grow more complex.

A Five-Phase AI Maturity Journey

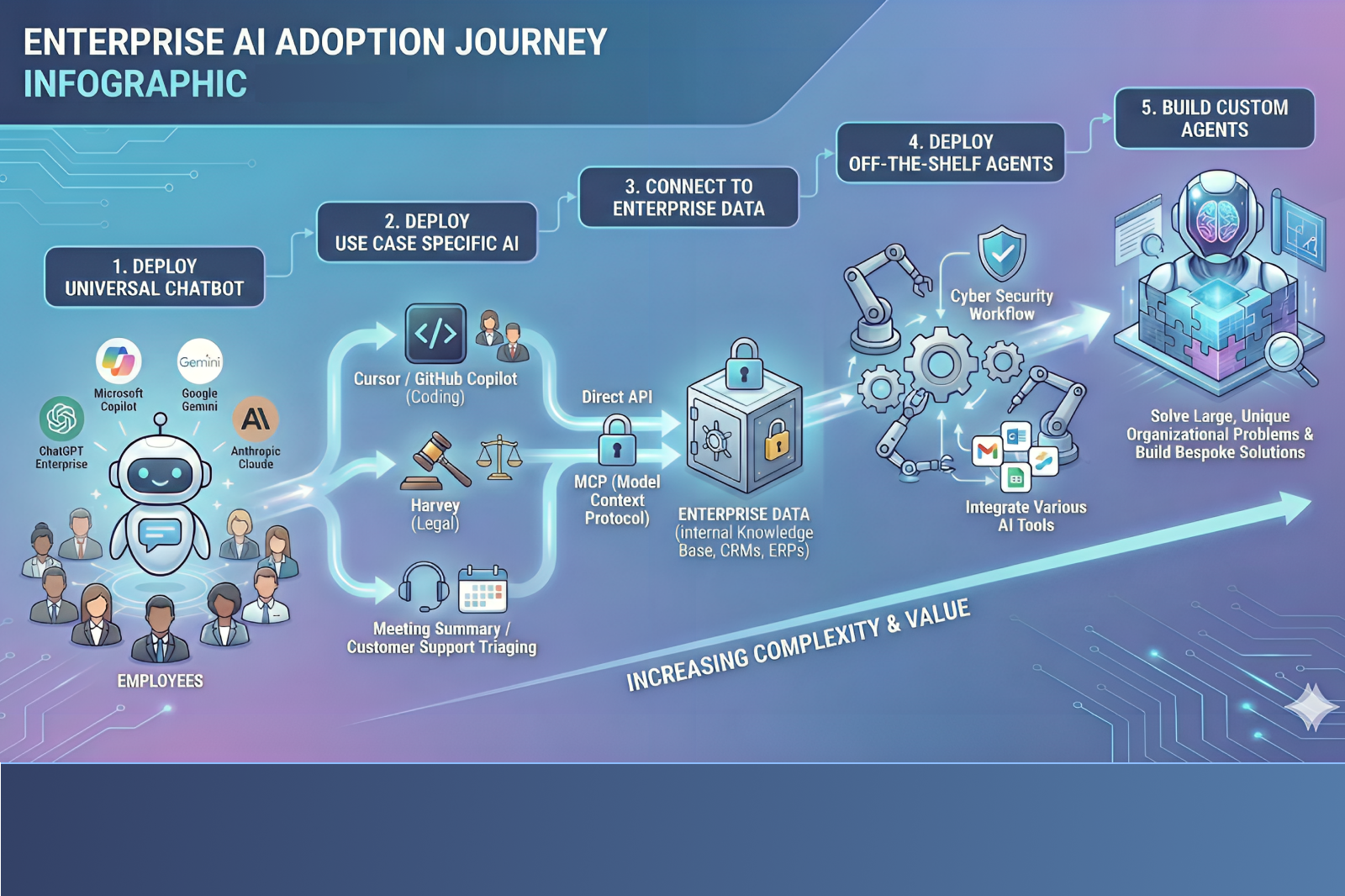

Based on what we are seeing across customers and the broader market, enterprise AI adoption generally progresses through five phases.

The first phase involves universal chatbot deployment. These are general-purpose assistants such as Copilot, ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini, typically procured to improve workforce productivity.

The second phase introduces vertical or task-specific AI. These tools are designed for particular functions such as software development, legal research, marketing, or customer support.

The third phase begins when enterprises connect AI systems directly to enterprise data. This may happen through APIs, OAuth-based connectors, or MCP servers.

The fourth phase involves off-the-shelf agentic applications. These agents do not just respond to queries, but actively perform actions on behalf of users or the organization.

The fifth and most advanced phase is the development of custom-built agents. These systems often plan, reason, and execute autonomously across multiple systems.

Each phase unlocks additional value. Each phase also expands the security surface in different ways.

Image Preview Text: The diagram below illustrates how most enterprises progress through AI adoption, and how complexity and risk evolve at each stage.

Phase One: Chatbots, Hallucinations, and Enterprise Hygiene

The earliest concern enterprises raise about chatbots is hallucination or misinformation. This is best understood as an education problem rather than a security failure. AI systems can make mistakes, and employees need to be trained accordingly.

In practice, this means encouraging verification, requesting sources when appropriate, and ensuring that AI-generated output is not treated as authoritative in high-risk contexts.

A more concrete concern is the use of enterprise data for model training. When employees paste proprietary source code or sensitive documents into AI tools, enterprises must ensure that this data is explicitly excluded from training. Most enterprise-grade AI products support this today, but enforcing the setting consistently is not always straightforward.

Some controls are applied centrally, while others require enforcement at the endpoint level. This is where enterprise device management becomes foundational. Tools that manage endpoints at scale allow organizations to enforce AI-related settings consistently across their workforce. This theme, enterprise manageability as a risk mitigator, will recur throughout every phase of AI adoption.

Treating AI Like Any Other Enterprise Application

Once basic safeguards are in place, AI tools need to be governed like any other SaaS application. This includes federated single sign-on, elimination of local accounts, auditing of privileged identities and operations, session monitoring, and well-defined joiner, mover, and leaver workflows.

At this stage, identity governance and identity threat detection become essential. In many ways, the identity challenges introduced by AI mirror what identity teams faced during the large-scale adoption of SaaS. These same patterns have already played out in real-world compromises, where identity sprawl across connected applications expanded attacker blast radius.

Shadow AI Is a Familiar Problem

Even when enterprises provide approved AI tools, employees often experiment with alternatives they discover through news, social media, or peers. This behavior is best understood as shadow IT, rebranded as shadow AI.

Organizations have long relied on secure access service edge platforms and device trust controls to detect and limit unsanctioned SaaS usage. Those same approaches apply here, but only reliably on managed endpoints. In environments where employees use unmanaged or personal devices, shadow AI remains difficult to fully control.

Safe AI adoption ultimately depends on layered controls, device trust, and realistic expectations about what can and cannot be enforced.

Phase Two: Vertical AI and Increased Impact

The second phase introduces task-specific AI, particularly in software development. Coding assistants are now among the most widely deployed AI tools after general-purpose chatbots.

Most of the controls from the first phase still apply. Enterprises must ensure that proprietary data is not used for training, that authentication and provisioning are well-governed, and that privileged access is monitored.

The difference lies in impact. A hallucinated chatbot response may waste time. A faulty code suggestion can introduce vulnerabilities into production systems. The blast radius grows, even though the underlying control framework remains largely familiar.

Phase Three: Connecting AI to Enterprise Data

Phase three is where AI adoption becomes meaningfully more complex. Once enterprises connect AI systems to internal data, they must confront difficult questions about access boundaries and authorization.

AI systems may connect to enterprise data through APIs, OAuth grants acting on behalf of users, OAuth grants acting on behalf of the tenant, or MCP-based integrations. Each approach introduces familiar challenges around credential governance, privilege scoping, and monitoring. These dynamics reflect broader early inflection points where AI intersects directly with identity systems, changing how access is exercised at scale.

What changes is how access is exercised. An AI system with broad data access can unintentionally bypass human access controls. A user who cannot view payroll data directly may still receive sensitive information if a chatbot has access and responds without enforcing the same authorization logic.

This is not a hypothetical concern. It is an authorization design problem.

MCP Deployment Considerations

MCP introduces additional considerations depending on how servers are deployed. Local MCP servers running on user devices pose clear risks. Credentials and API keys may be stored on endpoints without centralized visibility or control. For most enterprises, disallowing local MCP servers through endpoint management is the safest default.

Remote MCP servers hosted alongside SaaS applications are generally lower risk. These servers typically rely on OAuth-based access and inherit much of the provider’s security posture. Even so, enterprises need to understand what privileges are granted and whether write operations are permitted.

Read-only access may be acceptable in many cases. Write capabilities significantly increase risk and require stronger oversight.

Phase Four: Off-the-Shelf Agents and Authorization Models

As enterprises adopt prebuilt agents, authorization models become central. Some agents act fully on behalf of a user, inheriting all of their permissions. Others operate with more narrowly scoped access. Some are granted tenant-wide access across organizational data.

As agents gain the ability to execute actions, connectors and MCP servers become powerful control points. Without strong monitoring and guardrails, these systems can perform unintended actions at scale.

Phase Five: Custom Agents and the Need for Guardrails

The final phase involves custom-built agents, often with their own identities, operating across cloud, SaaS, and on-premises systems. If these agents execute deterministic workflows with predefined constraints, risk can be managed.

The challenge emerges when agents reason, plan, and act autonomously. In these cases, human-in-the-loop controls become essential, particularly for write or destructive operations such as committing code, modifying data, sending emails, or archiving systems.

In practice, even human approval may not be sufficient. We increasingly see architectures that use an LLM as a judge to evaluate the risk of an action and provide context to the human approver before execution.

Identity systems play a critical role here. They provide visibility into agent behavior, track execution paths, categorize risky operations, and enforce approval workflows. They also enable detection of anomalous patterns, such as approvals occurring too quickly to reflect genuine human oversight.

For security leaders, confidence in agentic systems depends on knowing that these guardrails cannot be silently bypassed.

Closing Perspective

Agentic AI does not only introduce entirely new security problems. It amplifies existing ones around identity, authorization, privilege, and monitoring, and it does so at machine speed.

Enterprises that treat AI adoption as a maturity journey rather than a binary decision are best positioned to extract value safely. Identity is not an add-on in this world. It is the control plane that makes agentic systems governable.

In follow-up posts, we will examine specific failure modes in greater detail and explore how many of them could have been prevented with the right architectural choices.